Wherever you go in Japan, you’re sure to hear tales of the legions of yokai roaming the countryside, gliding through the air, lurking under the surface of the water, or even sneaking around in every shadow. Although many of you may be interested in Japanese yokai, perhaps you don’t know a lot about those gruesome creatures. In this serialized feature, we’ll try to entice them out of their hiding place and introduce some of their features that will take your breath away.

Making an entrance here are the yokai whose appearances have been captured in paintings, names have been identified, and presence has been confirmed since the Edo Period (1603–1868). As for animals with the ability to shapeshift, often regarded as one type of yokai, such as tanuki (raccoon dog), kitsune (fox), and mujina (badger and civet), we’ll discuss them later―they are very difficult to recognize since they can take on any form they wish.

Let’s take a quick look at what kinds of yokai inhabit Japan before scurrying away from the sunlight.

Yokai with Strong Connections to Regional Tradition

Some types of yokai will only make their appearance under certain circumstances. For example, there are yokai that only inhabit a specific region. On the other hand, there are some yokai that we can meet all across Japan but only creep out at a designated place and/or time.

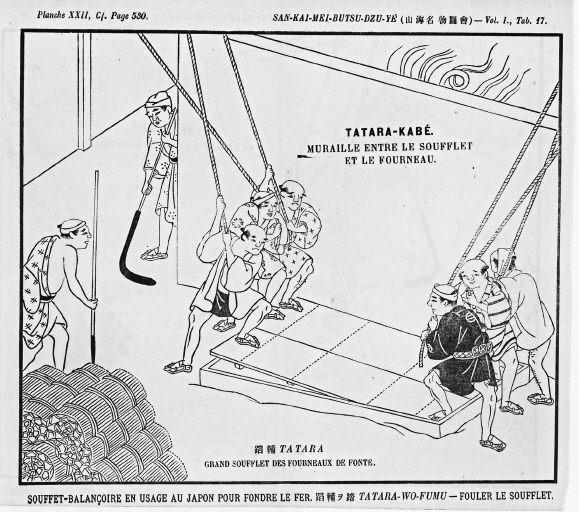

Yokai that are only encountered in a specific region have strong connections to that region’s folklore, beliefs, taboos, and traditions. One example of such yokai would be Ippon-datara (one-legged bellow), which only appears along the Hatenashi mountain range extending over Wakayama and Nara prefectures. It is said that Ippon-datara has a body resembling a boar covered with coarse hair, two arms, one leg, and one red eye.

The appearance of Ippon-datara is said to be connected with tatara iron manufacturing conducted in the region. A tatara worker uses one foot to step on a tatara (foot bellow) and one eye to watch the fire. While stepping on the tatara, the worker is continuously exposed to high temperatures, causing damage to the leg over time. Moreover, keeping watch over the fire can cause the workers’ vision to gradually decrease eventually leading to blindness. Now you can see how Ippon-datara’s physical description represents the tatara iron manufacturing tradition in the region.

(Illustration: Omega Communications)

(Image: International Research Center

for Japanese Studies)

Yokai with Strong Connections to Places and/or Situations

Next, we’d like to introduce yokai associated with specific type of place and/or situations. Let’s take a look at Kappa (river child) and Kawa-Akago (river baby) for a start. Many of you might have heard that Kappa live in the streams or watering holes but did you know the presence of a Kappa makes the difference between a pond (ike) and a marsh (numa) in Japan? If a Kappa lives there, the watering hole would be regarded as numa*4.

Now, imagine you’re trudging along down the street all alone at midnight. Suddenly, the shrill cry of a baby pierces the silence around you. If there is a river beside you there could be a Kawa-Akago*3 crawling around the riverbank crying. If it just happens to be raining, an Ubume (the ghost of a woman who died in childbirth) overcome with sorrow carrying a baby would appear out of the darkness instead. However, if there’s a rock rolling around wildly and you can also hear the sound of a woman sobbing there’s no mistake that the one crying is Yonaki-Ishi (night-crying stone). These yokai appear on designated stages and have distinct roles to play.

(Image: International Research Center

for Japanese Studies)

(Image: International Research Center

for Japanese Studies)

In the next article, we’d like to discuss tsukumogami (tool ghosts and monsters) and yokai that were brought to life in stories. We are looking forward to meeting you again next time.

[Footnotes]

*1 Gazuhyakkiyako by Toriyama Sekien was the primary source for yokai names and descriptions here.

*2 On some occasions mujina is used to indicate tanuki but we have classified them separately here.

*3 According to the Gazuhyakkiyako, Kawa-Aakago is a type of Kappa.

*4 This is simply one of the theories; there are many ike (ponds) located across Japan known as Kappa Ike.

*5 Ubume is the ghost of a human but there is also a legend about a yokai bird called Kokakucho, using the same kanji, “姑獲鳥.” In this case, we are adhering to the notations used in Gazuhyakkiyako.

[Reference]

Ehon Hyakumonogatari—Tosanzin Yawa—, Takehara Shunsen, Kokushokankokai,1997.

Gazuhyakkiyako, Toriyama Sekien, Kadokawa Sophia Bunko, 2005.

Zusetsu Nihon Yokai Taizen, Shigeru Mizuki, Kodansha+α bunko, 1994.

Yokai.com, September 27, 2019.

We are accepting applications for writing tourism and cultural articles in Japanese and/or English, multilingual translations and other services. For inquiries, please contact us:

Tel: (+81) 3-6902-9030

Email:

Note: Unauthorized copying and replication of the contents of this site, text and images are strictly prohibited. All Rights Reserved.